The Organization of the Gravely Concerned Nations

In February 2024, reports emerged allegedly connecting UN workers to Hamas terrorist attacks on and kidnappings in Israel. These accusations added another brick in the wall displaying how the United Nations (UN) has been losing its credibility. Before that, in March 2023, the International Criminal Court put Russian President Vladimir Putin on a wanted list on war crimes charges. Subsequently, the UN acknowledged that Russia had forcibly deported at least several hundred children from Ukraine. These deportations meet the definition of genocide under the UN Convention. However, in just two weeks, in April 2023, Russia took over the presidency of the UN Security Council (UNSC), the highest body of all international institutions. This temporary transition of the UNSC presidency could be seen as a formality, as each UNSC member, both permanent and non-permanent, has a right to hold the presidency for one month. What is not a formality are the ongoing investigations of Russia’s war crimes in Ukraine. If the world wants to prevent the global security and cooperation system to turn into a bad April Fool's joke, the UN must change.

Vandalised UN cars in Kyiv, Ukraine. Photo: yo_syp.

The price of old compromises

Before we start advocating for change, we need to understand how we ended up in a world where a terrorist state holds the key position in the global security system. Many rules of the modern world order were introduced as temporary compromises between the western democratic world and the totalitarian Soviet empire and, later, the totalitarian Chinese state. The UN was not established to pursue the creation of a just world. The UN was established by the criminal USSR as much as by the democratic United States, and, hence, had very cynical goals. In a narrow understanding, the UN sought to be a mechanism for the final destruction of the German and Japanese militarism and the subjugation of a few other countries. That is why the UN Charter has Article 53, which refers to "enemy states" against which force can be used without a Security Council resolution, and Article 77, which refers to the annexation of territories from "enemy states." Secondly, the UN was a tool for restructuring the world in favor of the WWII victors. Therefore, any state that fought during World War II against one of the founding powers of the UN (Article 53(2)) became an "enemy state", and many enslaved peoples seeking freedom turned into nations under the “trusteeship” of the former colonial powers. In the long run, the UN would have to consolidate the hegemony of a few major victors, as they guaranteed themselves a large-scale advantage over all others by creating and immediately seizing the powers of the Security Council’s permanent members.

The US, UK, French, and Soviet generals at a joint parade in Berlin, 1946. Deutsche Fotothek. CC-BY-SA-3.0-DE

These are the background preconditions that framed the modern structure of the UN and its Security Council. These preconditions also forged the UN Charter, the most stringent international treaty limiting the right of states to war. The Charter’s Article 1 declares the preservation of peace as the main UN purpose. Its Article 2 prohibits the UN members from resorting to force in international relations, while at the same time obliging members to fully support UN measures against violators. The only body that can introduce binding preventive measures is the UN Security Council. Since almost all states in the world are members of the UN, this leads to two conclusions. First, no country in the world has the right to declare war. Contrary to popular legend, a war cannot “be declared” in terms of modern law. One can start an armed aggression (which would be a severe violation of the UN Charter) – with or without a declaration, as any declaration does not change anything. Such aggression in its turn could be responded with self-defense, either by one state or collectively. As the UN Charter authorizes this self-defense per se, it also does not require any "declaration". Second, in all other cases, only the Security Council has a right to initiate military or other forcible actions within the framework of precautionary measures without violating international law. All UN members must fully participate in implementing these measures.

Thus, the Security Council is a unique institution that retained the right to use violence against UN members, and even to force other countries to join such actions. It comes as no surprise that the WWII victorious states not only guaranteed themselves permanent membership in the UN Security Council, but also combined this membership with the right to veto. In addition, they also did not develop a UN Charter mechanism to deprive a UN Security Council permanent member of this mandate and/or a veto right. Is this system unfair? Obviously, it is. First, it violates the principles of equality between the sovereign states by dividing them into first- and second-class states. Second, it also immunes the five UNSC permanent members to any preventive measures, since such measures can only be declared by the same five countries comprising the UNSC. This contradicts the legal principle of Nemo judex in propria causa - no one can be a judge in his own trial.

A white commanding officer, black soldiers. UN troops in MONUSCO mission, 2018. MONUSCO Photos, CC-BY-SA-2.0

The fallacy of simple solutions

If the UN system is unfair, are there simple and effective ways to improve it? Even if Russia is pushed out of the UNSC, it is hard to imagine that the other permanent members will agree to change the UN Charter and to strip themselves off their veto power. Furthermore, if the UNSC were to adopt decisions by simple majority, without the veto power of the permanent members, it risks to start adopting even more politically-motivated decisions. Such a Security Council could easily approve preventive measures against Israel (the vast majority of UN General Assembly resolutions are seemingly anti-Israel) and even against Ukraine. What explains this UN proclivity to politically-biased decisions? There is an inherent weakness in the UNSC composition. The UNSC includes, in addition to the five permanent members, 10 non-permanent members. These are five countries from Africa and Asia, one country from Eastern Europe, two countries from Latin America, and two countries from Western Europe or other regions. Can such a set of countries form an anti-Ukrainian or anti-Israeli coalition? Yes, if it includes, for instance, China, Belarus, Venezuela, Syria, Nicaragua, and Hungary.

It is true that the UNSC is unable to reach a consensus against Russia due to the country’s veto power. But this is the exactly the point. The UNSC system was designed to block decisions, not to make their adoption easy. A UN that is constantly gravely concerned, but does nothing, is not a mistake, it is an intended quality of the institution. From a point of view of the UNSC permanent members, the unfair empowerment of some countries in the UNSC decision-making process is the intended advantage of this system. This system worked (almost) perfectly until a terrorist state with a unique level of criminality found itself among the permanent members of the UNSC. Moreover, such a system is certainly preferable to the one that would give Assad's Syria or Kim's North Korea the same weight as to Canada, the United States, or the United Kingdom.

Therefore, when seeking to strip Russia off its permanent seat in the UNSC, one must acknowledge that a radical reform of the UN, that would strengthen its intervention mechanisms and weaken intervention barriers, is not always desirable. A new international security system, more comfortable for Ukraine and safer for Europe, should probably focus not on reforming the UN but on strengthening regional military alliances, to which Ukraine will belong, along with other democratic countries. The problem with the modern UN is not the disregard of the principles of the formal equality of states or fairness in the distribution of powers. The problem lies in the fact that international politics sooner or later faces the question of the just use of force and has to make up its mind quickly and decisively.

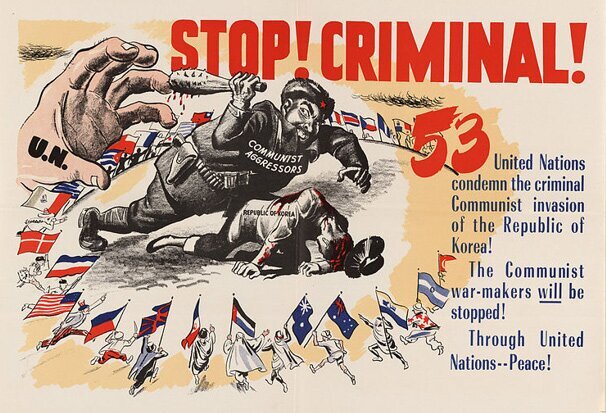

"Stop! Criminal!" a Cold War poster cheers the UNSC decision to impose collective measures against the Soviet Union in Korean War.

How to curb wars

The history of international law has seen two millennia of thinking through the rules of violence. The most brilliant minds were looking into how to limit and regulate violence. Already in the I century B.C., Cicero, in his treatise On Duties, formulated the necessary conditions for a legitimate war, which included: the war must be provoked by a violation of law, diplomacy should be sought to resolve the conflict before starting a war, the war can only be waged by a central political authority, and the goal of the war must be to restore justice. These thoughts shaped the debate on the justice and limitations of war until the early XX century.

In the XIII century, Catholic philosopher Thomas Aquinas developed his concept of a just war: it needs to be declared by a sovereign, it has a just cause, and its goal is to increase peace in the world, i.e., to achieve a more just order. In the XVII century, Dutch Protestant philosopher Hugo Grotius reinterpreted these rules and declared that all states should obey international law, which would determine the justice of war. At the same time, rules of engagement were being developed informally to limit the conduct of hostilities, such as the treatment of wounded, prisoners, or the use of various weapons systems. At the turn of the XIX and XX centuries, the leading powers signed the first conventions on the conduct of war, the Hague Conventions on the Laws and Customs of Warfare of 1899 and 1907, which were intended to limit the brutality of war.

World War I, with its use of toxic gases, automatic weapons, heavy artillery, and even tanks, demonstrated the inadequacy of this approach. The existing rules of warfare did not contribute to peace, and technological progress was moving faster than the limitations of treaties. For example, the Hague Conventions prohibited using balloon for attacks but said nothing about the use of motorized aircraft or poisonous gases. The creation of the League of Nations, an international security system established to prevent the outbreak of wars, was an attempt to overcome this paradox. The League of Nations obliged its members to conduct negotiations in the event of conflicts and created mechanisms to resolve disputes. These mechanisms did not yet outright ban wars, but international opinion was obviously moving in that direction. In 1928, several states signed the Briand-Kellogg Pact renouncing wars as an instrument of international relations. However, these attempts failed to prevent a series of aggressions starting with the Italian invasion of Abyssinia, the Manchurian War, and later conflicts. Finally, in 1939 the League of Nations failed to stop either the Nazi Reich from attacking Poland or the USSR from attacking Finland. This unholy Berlin-Moscow alliance buried any attempt to create tools preventing wars and started World War II.

The Nazi and the Soviet tank troopers celebrate joint victory over Poland, 1939. Contando Estrelas, CC-BY-SA-2.0

The UN, created in 1945 after World War II, attempted not only to establish peace between the great powers but also to put a real end to wars. This attempt was not entirely unsuccessful, as the number of wars decreased significantly in the second half of the XX century. However, the UN failed to fully achieve its anti-war goal. Moreover, the most successful military actions of the past decades, for example, NATO's intervention against Serbia which stopped the genocide in Kosovo, were carried out without the formal consent of the UNSC but by the decisions to intervene on a humanitarian basis taken unilaterally or by a few countries. Just like Cicero two thousand years ago or Thomas Aquinas eight hundred years ago, Bill Clinton, who decided to bomb Belgrade, saw a moral justification of this intervention and had the goal to restore justice.

Are these values shared equally by most countries around the globe? Hardly. A large part of Africa or South America, despite the obvious evidence of Russian genocide and aggression, does not support Ukraine in its fight against the Russian invasion. Brazilian President Lula’s accusing Ukraine of starting the Russo-Ukrainian war is not the success of Russian propaganda but the sign of varying systems of values and sympathies. The notion of justice in the minds of the Brazilian left conflicts with the vital interests of Ukraine’s Irpin residents to such an extent that Ukraine’s security could be endangered by Brazil's vote in a strong UN.

Finally, is a large-scale UN reform even feasible? Today, UN law and institutions form an overlapping network of international structures and treaties, from nuclear energy to social issues. Additionally, the past two decades saw the largest number of treaties concluded by the mankind, and most of them are directly or indirectly related to UN law. The UN Charter is also integrated into the legislation of regional unions, including the Treaties of the European Union. Even EU sanctions legislation fully depends on and refers to UN law. Abolition or radical reform of the UN is unlikely to have serious implementation chances in such circumstances.

North Korea's dictator Kim Jong Un under a Russia's genocidal emblem "Z", visiting Russia's missile launch site "Vostochny". Kremlin. CC-BY-4.0

Additional mechanisms

The UN's inaction is damaging in certain areas of Europe's vital interests, for instance, in countering Russian aggression. But does this UN characteristic imply the mandatory UN abolition? Or does it rather nudge to find an effective answer for challenges that directly affect the vital interests of the region? The European countries should prefer to decide their fate individually, without involving Brazil’s President Lula or China’s President Xi in a reformed UN. Hence, Europe will benefit from a regional organization that puts the UN aside by taking advantage of its incapacity and laziness.

Will NATO become such a structure for Ukraine? It is a good but not the sole option. The latest comments of US presidential candidate Donald Trump on NATO’s Article 5 demonstrate that NATO should not be left as the only ultimate tool to preserve peace in Europe. Besides NATO, Ukraine could join a few other military alliances that would make decisions at different levels. For example, a regional military alliance with Poland, the Baltic states, and Czechia, could give Ukraine flexibility to deal with conflicts, when NATO, an organization with a different set of resources and solidarity with Ukraine, requires more processing time. During a border crisis with Belarus, when Belarus and Russia weaponized refugees to destabilize the EU, Poland did not seek help from the UN or NATO but coordinated its actions directly with similarly affected Lithuania. Ukraine can also create such alliances to increase its military and diplomatic maneuver capability in the future.

At the same time, although the UN system is not very capable in preventing wars, it could effectively deal with legal consequences of such wars. Yes, the UNSC failed to stop the genocide in Rwanda and did not intervene militarily in the genocide in Kosovo. However, the UNSC has established tribunals for both former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. The UN has plenty of shortcomings that prevent it from responding quickly and decisively to military challenges, such as the need for consensus decisions, the existence of many veto mechanisms, the diverse interests of its members, and the presence of non-democratic regimes. However, these very same shortcomings make such tribunals more legitimate in the eyes of those UN members who would never approve a UN military intervention. This is why, after Ukraine’s victory, the UN, which almost never intervened in the Russo-Ukrainian war, will likely have no problem with creating a legal tribunal to prosecute war criminals for violating international law on the territory of Ukraine.

The current global system of security and international cooperation is neither effective nor fair. It is worth criticizing and worth investing efforts in compensating for its shortcomings. At the same time, the global security system can and should be radically changed. Even the United Nations, founded in response to the horrors of World War II, did not outright reject the ideas of the League of Nations, which had disappeared by that time. On the contrary, the UN strengthened certain features of the League of Nations and brought them to a new level of authority. Similarly, any reform of the UN will likely bring some already existing UN features into the new system. Hence, Ukraine needs to increase its influence in the existing UN institutions to be able to force the UN to accept measures favorable to Ukraine. Only then should Ukraine seek radical changes of the UN structure. And remember that these changes will require a lot of time and effort.

This article was written for and first published at Tyzhden.ua

Did you like this article? Donate and support the European Resilience Initiative Center: