Russia’s Hidden Colonialism: Its Origins, Forms, and the Ways to Escape It

Speaking of colonialism, Russian officials traditionally chose the mode of denying colonialism of their own and blaming that of others. “Our country has not stained itself with the bloody crimes of colonialism,” wrote Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov in his programmatic article published in July 2022 [1] in several newspapers across the African continent as a part of the Russian informational campaign around Lavrov’s visit to Africa. Free-riding the Western anti-colonialist agenda and blaming the real Western crimes in order to present Russia’s alleged innocence is nothing new. The Soviet Union used this tactic massively, addressing all the really existing Western problems in its propaganda of the Soviet way of life. Gun violence, social problems, racism, and all possible scandals were broadly used by the Soviet media [2]. Still, it is important to see how the same narrative is used today. While Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov denied any Russian experience with colonialism, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin made the next step. In December 2022, Putin ordered the Russian Ministry of Education and Science “to include into the study and research plans of the scientific institutions and the educational facilities of the higher education, funded from the funds of the federal budget, scientific research on the history of the origin, development, and the consequences of the colonialist politics of the European nations in Africa and on other continents” [3]. This clear wish to cast colonialism as allegedly purely Western phenomenon (and sin) is, therefore, an idea shared and addressed by the very top leaders of Russia nowadays, as back in the 19th century, as Russian classic painter Vereshchagin created his "Crackdown on the Sepoy Mutiny", with brutal Brits executing brave Sepoy.

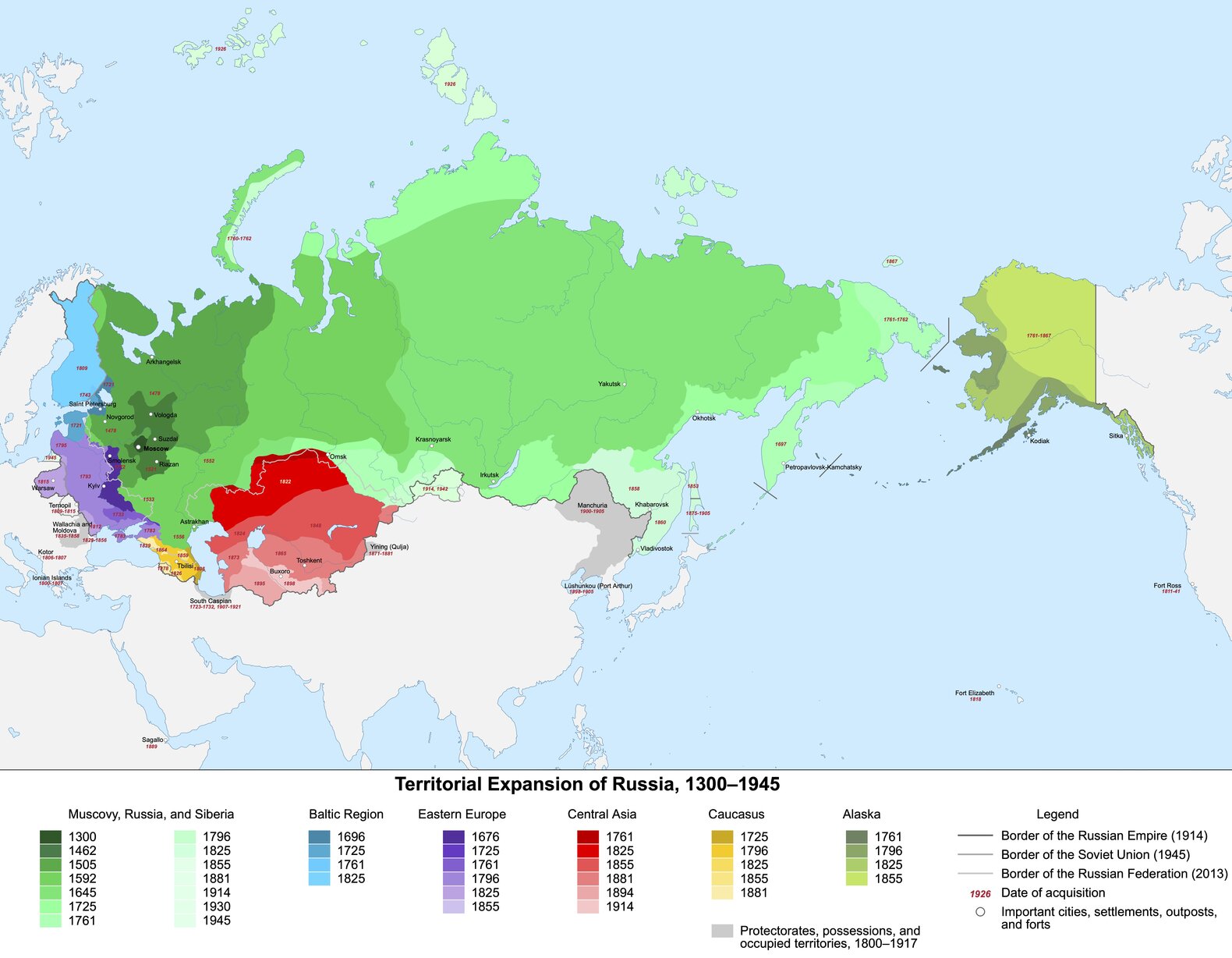

At the same time, while looking at the history of the Russian expansion, one cannot ignore the existence of the very clear parallels with the colonialism of the Western nations, including the same timeline, ways of expansion, and mechanisms of control over the colonized regions. The colonization of the American continents effectively started in the 16th century, with the wars on the indigenous people and the establishment of the Western forts first in South America and Central America (1538: the founding of Bogota, 1541: the founding of Santiago, 1565: the founding of Rio de Janeiro), and later on the territory of the modern USA (the founding of Jamestown in Virginia in 1607). Most expeditions of the Western colonizers were at least partly funded by private funds and aimed at conquering rich lands, establishing new trade routes, and expanding the zone of the crown’s influence. Most of the expeditions faced the existence of other nations – and even states – and used military violence to establish control over the new lands and eliminate the resistance.

"Crackdown on the Sepoy Mutiny", V.Vereshchagin, 1884

While the Western countries jumped into the expansion towards the Americas, Africa, and Asia, on another side of the globe, the Czar of Muscovy, Ivan IV the Terrible, opened for himself the same way of expanding the borders of his state. Yet in the 1540s, the borders of Muscovy were barely anything compared even with the nowadays “European part of Russia.” Muscovy did not even control the Volga region, competing there against the Khanate of Kazan. Ivan the Terrible led three campaigns against Kazan in 1547–48 and 1549–50 until he finally conquered Kazan in 1552 (this day is until now remembered by Tatars as a day of a national tragedy, as after the conquest of Kazan a significant part of the population was slaughtered). In 1556, Ivan the Terrible took Astrakhan – the capital of the Astrakhan Khanate in the Lower Volga, on the shores of the Caspian Sea (in 2022, the Russian strategic bombers set off from Astrakhan to bomb Ukraine). Still, those steps were just the warming-up for the state expansion under Ivan the Terrible. The most successful and massive Russian expansion initiative was the colonization of Siberia. The fundamental event of it took place in 1581-85, as the Stroganov family of private merchants hired Yermak Timofeyevich, a warlord and mercenary, to eliminate the influence of the Siberian Khan Kuchum, who was formally a vassal of the Muscovy but demonstrated his growing independence amid Russia’s misfortunes in the Livonian war. In the following four years of the wars, called in the Russian historical tradition “the Siberian expeditions of Yermak” (Sibirskiye pokhody Yermaka), the Russian mercenaries exploited their advantage of having guns and took under control large territories along the rivers Irtysh, Ob, and Tobol. Until the early 17th century, the Muscovy had dramatically expanded its territory and conquered not only the Volga region (now considered “heartland Russia”) but also the Ural Mountains and even went further hundreds of kilometers into Siberia. Still, the territory of most of Siberia, not mentioning the Pacific coast, and both Kamchatka and Chukotka peninsulas remained out of the Muscovy’s control.

"Conquest of Siberian by Yermak Timofeyevich", V.Surikov, 1895

The quantum leap of Muscovy’s expansion took place in the 1630s, as – at the same time when the Western powers had overtaken the control of the Americas – the Muscovites took Siberia. From 1628 (founding of Krasnoyarsk) till 1649 (founding of Anadyrsk in Chukotka, not to mix with the nowadays existing city of Anadyr in the same region), the Muscovites expanded their control over the territory of more than 8 million square kilometers, effectively having conquered not only the whole of Siberia but also the Pacific coast and the polar regions. The newly obtained land was comparable with the territory of the nowadays USA (9.5 million square kilometers). The expansion was so effective that in the 1750s, the Russians (Czar Peter I had already renamed the state Russia) founded their colonies in Alaska and even the settlements in California (Fort Ross) and on the Kaua’i island of Hawaii (Russian Fort Elizabeth).

Speaking of the Muscovite / Russian expansion, one needs to stress that even modern Russian scholars do not try to hide the motives and the ways of colonization. Aleksandr Kazarkin from Siberian Tomsk University writes, quoting another Russian scholar Sergey Bakhrushin: “Normally, a military operation would take place before the indigenous people were forced into paying tribute. [After that,] the market in Krasnoyarsk was not selling mainly furs as usual, but the forcibly taken yasir [slaves, including female slaves sold as sex slaves].” He adds further: “The Russian colonization of Siberia is divided into three phases: military operation in order to force the locals to pay tribute; agricultural stage; and industrial stage. The core problem here was the acculturation [of the local population]” [4]. Interesting that the Russian scholar Kazarkin effectively blames the locals – “non-Russians” – for the Russian atrocities, as he writes: “taking hostages, forcing into pledging loyalty, terror against strong ones… – the [Russian] Cossacks took all these measures from the Horde” [5].

This point of view is extremely important for the further understanding of Russian colonialism and its modern perception in Russia. Practically, we deal with total denial of any crimes committed by the Russian colonists in the past or by Russia nowadays. The atrocities are either “learned from the locals” or did not happen at all. Kazakh-German scholar Botakoz Kassymbekova, Lecturer in Modern History at Universitat Basel, points out, that there are two models of colonialism: one is oversea colonialism based on control of workforce, and another one is a genocidal settlers colonialism based on control of the land.

"The difference between settler colonial empires and extractive overseas empires lies in the relationship to land and labour… for settler colonial empires securing territory is the key purpose… in settler colonial empires in order to secure land for settlement you try to free the territory from the indigenous populations… using two modes… the first one is genocides… the second one is assimilation of local populations … when you assimilate people … they don’t claim the land back… so this very violent process of assimilation took place.” [6]

Territorial Expansion of Russia, full file: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4a/Territorial_Expansion_of_Russia.svg

As the world is mostly familiar with the British model of colonialism, an oversea colonialism based on workforce control and segregation, the Russian model of colonialism, based on eradication of the local population, settling of Russian population, and acquisition of the remaining indigenous people, is not being identified by a broad public as colonialism at all. It is not a surprise therefore, that the Russian officials repeatedly addressed the “overseas model” to blame colonialism, but said no word about the Russian settler colonialism. In this tradition, Minister Lavrov clearly twists reality in his cited article, claiming that Russia has never committed any crimes of colonialism. This statement has been typical for official Russian politics and science for at least 150 years. The idea that it was the Brits who were colonialists and exploiters, whereas the Russians were humanistic and “helped” the local ethnic groups develop their societies, was first mentioned at least in the mid-19th century. Russian military geographer Mikhail Venyukov wrote in 1877: “We are not the Englishmen who try not to mix in India with the local race. Our power is different; we assimilate the local nations, in friendly fusion with them” [7].

Of course, this was not true. Even in their own reports, the Russians mentioned the brutality of their colonization. “The Circassians hate us. We pushed them from their comfortable grass plains, pillaged their villages, destroyed the whole tribes,” wrote Russian poet and imperialist Alexander Pushkin in the early 19th century in his “A Journey to Arzrum” notice. “The tranquility of Asia directly depends on the number of the people we massacred there,” wrote Russian General Skobelev in his letter in the 1890s. “We killed two thousand Turkmen in Geok-Tepe, those who survived will never forget it. With our sabers, we cut everybody we could reach,” he added [8]. The oppression of the colonized nations continued well into the 20th century. So, in 1916, amid World War I, the Russian army brutally suppressed the protests against the forcibly conscripted Kyrgyz, provoking the mass escape of the Kyrgyz from Russia, later called Urkun (the Exodus). According to different studies, between 100,000 and 250,000 Kyrgyz died amid this forced migration because of bad weather and hunger [9].

"Ukrun", modern painting

Soviet Russia just continued the traditions of colonization. Only in the early years of the Soviet reign, it proclaimed the so-called korenizatsiya (rooting) politics, providing the ethnic minorities the right to freely use their languages and live their culture. This politics should have helped the Russian authorities win the hearts and minds of the colonized nations as potential allies against the Czarist sympathizers. But as soon as there was no more need for this alliance, the russification of the colonized nations returned to the former Czarist patterns.

The forced russification of the colonized nations included many typical tactics. Regarding the smaller nations, the Soviets tried to eliminate national self-identification by forcibly taking children out of their families and putting them into closed educational facilities with no contact with their parents. This practice, typically used against the nomadic nations in Siberia, led to several uprisings in the 1920s and 1930s, like the Kazym uprising and Tunguska uprising of the Khanty [10] and the Tungus Evenki [11] respectively, both brutally suppressed by the Russian troops.

The “bigger nations” were targeted with other, less violent but effective methods. For example, in the 1930s, most national languages using non-Cyrillic alphabets were forcibly reformed in order to unify them with the Russian language. For example, amid the reform of the Tatar language, the graphic was changed twice within ten years. In 1929, the Arabic-based alphabet was changed into the Latin one, and in 1939, within just three months, a new, Cyrillic-based alphabet was forcibly introduced [12]. The reform had some hidden tricks making the local language vulnerable to mocking and oppressing. The new graphic did not correctly reflect the phonetics of the Tatar.

Although the Tatar language has 42 phonemes, only 39 letters were created (33 basic Cyrillic letters and 6 with diacritics), leaving a grey zone for pronunciation. Many letters were assigned with quite different sounds than those in Russian. For example, even though there is no sound “ch” in Tatar but there is the sound “shch,” the new Tatar alphabet was given a letter that is associated with “ch” in Russian (despite the fact there is a letter associated with a “shch” sound in Russian). This created additional complications for the Tatars to speak clear Russian, marking them with the “Tatar accent.” In other Turkic languages (like the Bashkir language), the letters were assigned with other sounds making communication between the Tatars and Bashkirs more complicated. As in the 1930s, most non-Cyrillic alphabets of the languages of the colonized nations were forcibly russified, and the following generations of these nations were doomed to be unable to read the national literature published before the reforms using Arabic or Latin alphabets. This change impacted the Kabardin-Circassian, Tatar, Bashkir, and Kazakh languages, as well as all the languages of the Siberian nations and the nations of Dagestan. At the same time, the “national operations” by the secret police NKVD deliberately targeted national elites of the colonized nations, killing political activists, journalists, historians, book authors, and poets.

A pro-Tatar language demonstration in Tatarstan in later 1980s

The Moscow-initiated linguistic reform also purged the local languages from original scientific and technical vocabulary, replacing the original words (for example, in Tatar, the word for the automobile) with their Russian equivalents, enabling racist statements like “you have not even had a word for a car before the Russians came.” This basic racist attitude has remained popular among Russians until now. In his classic text about the role of Russians in the nation building, Russian nationalist actor and writer Mikhail Zadornov made his sarcastic racist joke: “The Russian barbarians invaded middle-age-level Asian villages, and once they had robbed them, there were only libraries, theaters, and cities left behind them” [13]. The process of the russification of the local languages has reached such a point that in the 1990s, a group of Tatar linguists had to launch a magazine Fen hem Tel (Science and Language), trying to revive the scientific vocabulary of the Tatar language, erased by Moscow [14]. The publication of the magazine stopped in 2014 amid growing Russian oppression of the local languages.

The erasure of the linguistic ethnic identities was followed by political oppression. Within the Soviet power structure, the concept of “brotherly nations” was developed, with the role of the Russian nation as a “big brother” and all others as the “smaller brothers” who need to follow the lead of the Russian nation and accept its “natural” supremacy. This “need” of the colonized nations to be “guided” by the Russians was the reason for the sophisticated structures within the Soviet hierarchies. For example, the Communist Party committees in the national republics needed a formal First Secretary who was a representative of the local ethnic group, but a Second Secretary was an ethnic Russian, in order to control the First Secretary with a de facto veto right. Close to the end of the Soviet Union, this unwritten rule was violated once, as General Secretary Gorbachev installed Gennadi Kolbin, an ethnic Russian, as a First Secretary of the Kazakh Communist Party in December 1986, provoking mass unrest. The unrest was brutally suppressed by the army but demonstrated the fragility of the Soviet system based on ethnic hierarchies [15].

Soviet crackdown on Kazakh protests in 1986

The system of ethnic oppression and hierarchies perfectly outlived the Soviet Union and exists within the Russian Federation nowadays. Exactly as during the Soviet era and before, during Czarist Russia, the oppression forms a hierarchic society with the racially oppressed representatives of the colonized nations. The word nyerussky (literally: “non-Russian”) is essential for understanding this concept.

Effectively, being a “non-Russian” has nothing to do with citizenship. A “non-Russian” can be any citizen of Russia or a foreigner if he belongs to a different ethnic group, in most cases one with darker skin or hair. As this term is both racist and socially-oppressive, the representatives of the “richer” nations (like the Germans or the Swedes) can hardly be called “non-Russians”, but inostranyets (literally “a foreigner”, with a meaning “a rich foreigner with a social status”). A German of Turkish or African heritage, though, will hardly be an inostranyets, at least until their financial status is checked. The expressions like “Why are you acting like a nyerussky?” can be addressed to a Russian person with the meaning: “Why are your acting weird, stupidly?” The saying “there is some nyerussky waiting for you outside” means “There is a person of a lower ethnic group waiting for you outside” (clearly not a visit which should be treated with respect).

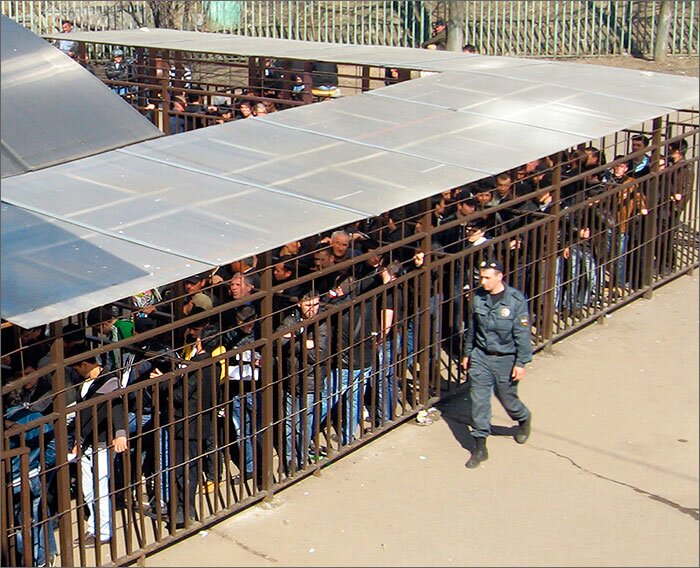

This system of internal racial hierarchies can be hard to understand for a foreigner (some persons who would be identified as a privileged Caucasian in the US can be severely discriminated against in Russia) but is naturally clear for anyone who lives in Russia. Russian citizens from the colonized nations face this system daily. Their papers can be checked by the police anytime; they can be detained, they do not get good jobs and even cannot rent a decent apartment. Until 2022, most Russian web services providing apartment rentals mentioned that the apartments will not be rented to “non-Russians,” of course including the citizens of Russia of a “wrong” ethnic heritage. The apartments were offered to “Slavs only” in most cases (here is to mention that the “Slavs” did not include Ukrainians as they were considered to be members of a lower ethnic group too). The biggest Russian web service “CIAN.ru” banned this racist practice only in December 2021, ahead of its IPO in the US [16]. In the following weeks, the rating of the CIAN app in the Google store was dropped by the outraged Russian users to 2.3 [17].

A Russian police officer and work migrants waiting for their work permits in a visa center in Moscow, Russia

The discrimination of the colonized nations, of course, includes the extermination of the local languages and cultures. Effectively it is done via making access to learning the local languages harder or even impossible. For example, only 47% of the schoolchildren of the Nordic ethnicities had classes for studying their mother tongue at school [18]. In Karelia, kindergartens providing services only in the Karelian language were banned because this “would cause ethnic segregation” [19], i.e., assimilation of the Karels is being seen as protection of their rights by the Russian courts. Effectively that meant that for smaller village kindergartens that had only one or two groups of children, only Russian-speaking groups could be created, as at least one group (probably the only exiting group in a small kindergarten) should be run in Russian only. In the Altai region, the local court has used the same argumentation banning the teaching of the local languages at the school as a standard class [20], forcing the teaching of the local language into free-choice class and de-facto eliminating any legal right of the children to demand this class (including the availability of a teacher, learning materials, etc.).

At the same time, speaking Russian with an accent can even trigger a criminal prosecution in Russia. In 2013, an ethnic Tuvinian male was routinely controlled in Petersburg, obviously because of his “non-Russian” appearance. As the police officers realized he spoke Russian with a heavy accent, they arrested him and started an investigation accusing him of providing them with a fake national ID [21]. The argumentation of the police was – no Russian citizen may speak Russian with an accent. The court accepted the case and investigated it, while the state attorney even claimed there was no such ethnicity as Tuvinian [22]. The person was not provided with a translator, as required by Russian law – exactly as a Komi person was denied to get access to a trial in the Komi language in 2021 [23].

Racially profiled arrests in Moscow, Russia

Language discrimination remains one of the most visible parts of the conflict between the colonized nations and Moscow. In 2022, in Tatarstan – one of the strongest national regions in Russia – local activists started a campaign against downgrading the Tatar language to the level of a “free-choice” class at school. They correctly believed this degradation would lead to the rapid decline of the financing for this class and attempts to persuade the families not to send the children to this “free-choice” class [24]. One needs to add that the idea of downgrading the classes of the local languages belongs personally to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Already in 2017, he claimed while visiting Yoshkar-Ola that “it cannot be tolerated that someone is being forced to learn a language which is not his mother tongue” [24], meaning the languages of indigenous people. At the same time, Putin called the Russian language “a natural spiritual skeleton” of the country and said that “everybody is obliged to know it.” Such an approach to local languages effectively means that almost none of the ethnic Russians learn the local languages after their degradation to a “free-choice” class, and a certain part of pupils from the colonized nations also decide not to invest their time in this class. After this, many schools just cancel the classes, arguing that there are not enough pupils for a class, and therefore they cannot finance a teacher. This means the elimination of the language within one or two generations, as the language is being reduced to purely family communication, therefore not social or scientific.

"Peoples' Friendship", a Russian propaganda poster

The pressure on the local languages reached such a severe level in some regions that it led to protest suicides. In 2019, Udmurt linguist and local university professor Albert Razin set himself on fire in front of the local parliament, protesting against the oppression of the local languages [26]. Still, language discrimination does not remain the only one. For many colonized nations, the oppression includes religious or other ways of discrimination. For example, in Moscow, over 250,000 Muslims celebrated the Uraza-Bayram holiday in May 2022, according to official Russian data [27]. As the multi-million city of Moscow has only four mosques [28], this annually leads to a huge concentration of Muslims around the two largest ones. The Moscow Cathedral Mosque attracts around 150,000 Muslims every important holiday [29], providing the Russian nationalists with impressive pictures of the “hordes of the Muslims” that “occupy” the streets in Moscow. As Islam is the traditional religion for many Russian-controlled regions, including Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, and the republics of the Northern Caucasus, this leads to clear discrimination against Muslims. To compare: there are 1,227 Russian Orthodox churches in Moscow, with 88 new churches constructed since 2010 out of the planned 200 new churches [30].

This kind of religious discrimination also takes place in the very regions. For example, in 2020-21, Russian mineral company Soda tried to start production of baking soda in Bashkortostan, effectively destroying a group of hills, Shikhany, which are seen as holy places by the local population. The attempt to destroy the holy places led to mass protests and even riots resulting in the Soda company abandoning its plans [31], but three leaders of the protests were sentenced to up to seven years in jail [32]. It is interesting that in 2022, amid the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, some groups which had their experience in mass protests in 2020–21 in Bashkortostan called for armed resistance against Russian colonialism [33].

Here, an important aspect of the colonization should be mentioned. Amid the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, ethnic minorities look to be the primary source of cannon fodder for the Russian army. This can have different reasons ranging from poverty in the ethnic regions up to the amount of young unemployed males. Still, it is clear that ethnic minorities pay the highest death toll for Russia’s war. The worst ratio of killed-in-action soldiers to the population is demonstrated in Tyva, with 28.4 KIA to 10,000 young males. In North Ossetia, it is 16.8; in Altai, 16.3; in Dagestan, 7.6. For comparison, in Saint Petersburg, the KIA to 10,000 young males ratio is 1.4, and in Moscow, it is 0.3. In other words, the chances of a young Buryat or Tyvinian dying in Ukraine are about 100 times higher compared to a young resident of Moscow (of any ethnical heritage) [34].

Graves of Buryat soldiers, killed in Ukraine. A screenshot from a Focus.UA video

The excessive mortality amid the war is just one of the most visible parameters of the imbalance of the Russian colonialist system. The same imbalance is visible in other aspects of daily life. One can compare the budgets of Moscow and “the rest of Russia,” as the Russians call the territory outside of the capital. For example, in 2019, the budget of Moscow reached 2,799 billion rubles, followed by 665 billion rubles in Petersburg’s budget. The next eight biggest cities in Russia had their budgets between 10.5 and 44.1 billion rubles [35]. This means the Moscow budget exceeded the budgets of all nine biggest Russian cities together by 3.3 times. Moscow’s urbanist projects cost 1.5 trillion rubles in 2010–19, compared to 1.7 trillion rubles spent on urbanist projects in the whole of Russia except Moscow over the same period [36]. Meanwhile, the most important sources of Russian wealth are located in the ethnic regions, like natural gas (the biggest amount of gas, 40.25 trillion cubic meters, in the Yamalo-Nenets autonomous district, followed by the Astrakhan region with a 4.4 trillion cubic meters deposit) [37] or oil, with the leading Khanty-Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets districts, and Tatarstan [38]. This clearly recalls the system of colonial rule in any empire, with the metropole enjoying its luxurious life at the expense of the colonized nations.

Based on the described situation, a natural question arises: is there any chance for the colonized nations to break out of the Russian Federation, the prison of the nations? To answer this question, one needs to examine two aspects of it. First is whether the proclamation of independence is technically possible for these nations.

According to the German state law (Staatsrecht) tradition, one of the most conservative worldwide, a sovereign state requires three characteristics to be accepted as existing. Those are the existence of the state nation (Staatsvolk), the state area (Staatsgebiet), and state power (Staatsgewalt) [39]. This means that to say that something is a state, one needs a nation that identifies itself with the state, whose members can not only self-identify themselves, for example, as Germans or French or Ukrainians, but also be able to say more or less clearly if an arbitrarily chosen person is a German, a French, or a Ukrainian. Secondly, a real state should have more or less clearly defined borders (the existence of disputed or uncontrolled territories does not apply here). Finally, this state should be able to apply its control to this territory. The current Russian Federation already holds many nations according to this very strict definition, as most ethnic republics are legally independent states that suit the strict definition of the German Staatsrecht.

Vladimir Putin opens Moscow's Cathedral Mosque in 2015, Kremlin CC-BY 4.0

For example, Article 1 of the constitution of Tatarstan [40] declares that Tatarstan is a democratic state. It also says that the current union with the Russian Federation is treaty-based and agrees on separation of powers with the Russian Federation – which means that this is effectively a treaty between same-rank sovereign actors, which provides both of them with the option to freely decide on what rights they reserve for themselves. Similarly, the constitution of Yakutia (Sakha) [41] says the same in its Article 1 and notes that the republic has a right to national self-determination. “Over a dozen other republican constitutions – from Altai in the far east to Karelia on the border with Finland – follow this norm: the republics are democratic states, which [currently] are parts of the Russian Federation. Most stress that the borders of the republics are clearly set and cannot be changed without their acceptance” [42]. Most of these regions proclaimed their independence in 1990 but have not finalized this process, as they signed agreements with Russia on the sharing of competencies. Still, this decision can be reviewed at any time, and there will be no reason for most world nations to ignore it, as the legal basis for independence is clearly available.

Second, there is a question of political reality – whether this decision to proclaim independence or address the issue of the already proclaimed independence will take place. Here one can recall how the breakup of the Soviet Union took place. The final steps to proclaiming independence were taken not by the dissidents but by the previously loyal Communist apparatchiks. It was the deputies of the Communist-run Councils of the Soviet republics who voted for the independence of their nations, and it was the First Secretaries of the national Communist parties who turned into the first Presidents of the free nations. The choice for them was clear: either to loyally glue to Moscow, where the disoriented General Secretary Gorbachev was losing his power, and sink with him, or to go independent and start to lead their own nations, with all the rights and privileges. The choice was simple. When in 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev turned into a political pensioner, his former subordinate Leonid Kravchuk became a president of a country with the world’s second nuclear arsenal, and another former subordinate, Nursultan Nazarbayev, turned into an autocrat with a prospect of over 20 years of presidency.

Mikhail Gorbachov's Resignation, 1991

The choice will be the same this time: out of a subordinate president of Tatarstan within the Russian Federation can emerge a new leader of a UN member nation, an oil exporting power with its legitimate place among the free nations. The feeling of injustice in the division of the oil and gas income, the burden of the deaths amid the Russian war on Ukraine, and the fear of the risk of sinking together with weak Moscow can spark the wish for independence. All the former insults, including discrimination based on language, religion, or race, will be remembered at this point and provide the independence movement with a moral justification.

Of course, these scenarios will not be identical for all the regions of Russia. Some regions will leave Russia more easily; first of all, the bigger and richer regions with homogeneous populations, like Tatarstan and Bashkortostan. They have a centuries-long history of resistance (Bashkirs used to revolt almost biennially in the 1730s–50s, so one day, the Bashkirs were banned from the job of a blacksmith in order to prevent the production of weapons. The leader of Bashkir chivalry Salavat Yulaev, a general at the Yemelyan Pugachev uprising under Catherine the Great, is a national hero in Bashkortostan until now, with streets, factories, and even a local ice hockey team named after him). They will leave Russia easily.

The second group of the nations are the smaller ethnic groups, some of them suffering from artificial borders drawn under Soviet rule. For example, the Circassians will have problems with their independence, as they were artificially united into the same region with the Karachays, a different nation, and split from the Adygs, who are basically the Circassians. Multiple nations of the Dagestan will also have their problem with developing one single political nation within the existing Russia-defined borders of the Republic of Dagestan. In addition, many nations of Siberia, like the Tuvinians or the Buryats, will suffer from economic and demographic problems, preventing them from the quick development of their own state structures.

Still, these problems are of a tactical character and cannot be compared with the costs of a centuries-long colonization of these nations, which led to racial and religious oppression, erasing of identities, and the deliberate destruction of the nations. A way to independence is a difficult and risky journey, but it is the only way out of the prison. Some nations who had tried it failed. But none of the nations who did not dare to step on this path reached any prosperity.

This article was written for and first published in a "Multidimensional Ruscism: The Beginning and the End" book, Kyiv 2023.

Did you like this article? Donate and support the European Resilience Initiative Center:

1. Lavrov, S. (2022) ‘Russia and Africa: a future-bound partnership’, The Pan Afrikanist, 22 June. Available at: https://thepanafrikanist.com/russia-and-africa-a-future-bound-partnership/

2. Порівняти: Зорин В. Противоречивая Америка: сценарии телевизионных передач и фильмов. М.: Исскуство, 1976.

3. Путин дал поручения Минобрнауки об истории религий России и европейском колониализме Африки // Регионы России. 13 декабря 2022. URL: https://www.gosrf.ru/putin-dal-porucheniya-minobrnauki-ob-istorii-religij-rossii-i-evropejskom-kolonializme-afriki/

4. Казаркин А.П. Этапы колонизации Сибири // Вестник Томского государственного университета. 2008. № 2 (3). С. 31–40. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/etapy-kolonizatsii-sibir

5. Там само.

6. https://updatefromkyiv.podbean.com/e/108-analysis-botakoz-kassymbekova-on/

7. Порівняти: Моррисон А. Аллергия России к своему колониальному прошлому // Eurasianet. 21 декабря 2016. URL: https://russian.eurasianet.org/node/63701

8. Атанесян Г. Лавров говорит, что Россия не запятнала себя колониализмом. Так ли это? // BBC News. 4 августа 2022. URL: https://www.bbc.com/russian/features-62414925

9. Панниер Б., Вальсамаки А. Столетие Великого Исхода кыргызского народа // Радио Азаттык. 1 мая 2016. URL: https://rus.azattyq.org/a/kyrgyzstan-urkun-1916/27709420.html

10. Тимофеев Л. Г. Казымская трагедия. Тюмень: Александр, 2007. URL: https://www.calameo.com/read/0047760432b9ecf1172a6

11. Ковелков С.И. Тунгусское восстание 1924–1925. Якутск: Изд-во ЯГУ, 2005. 134 с.

12. Измайлов И.Л., Каримов И.Р. Реформы письменности татарского языка: прошлое и настоящее // Журнал «Родина». 1999. № 11. URL: http://www.tataroved.ru/publication/npop/5/

13. Русские варвары // Михаил Задорнов. Официальный сайт. URL: https://zadornov.net/2014/06/russkie-varvary/

14. Шакирзянов Рашит Аглеевич // Музей истории КГАСУ. URL: https://museum.kgasu.ru/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=901:2021-12-09-08-15-32&catid=2:2013-02-11-09-00-17&Itemid=3

15. Лаханулы Н., Нурхасенулы К. «Избивали дубинками». Угасшие надежды в холодные дни декабря // Радио Азаттык. 17 декабря 2019. URL: https://rus.azattyq.org/a/kazakhstan-16-december-1986-memories/30329525.html

16. После американского IPO Циан запретил писать «только славянам». URL: https://smart-lab.ru/blog/746034.php

17. Ханенева В. Рейтинг ЦИАН обрушился после запрета сдавать жилье «только славянам» // Газета.ru. 8 декабря 2021. URL: https://www.gazeta.ru/tech/news/2021/12/08/n_16984363.shtml

18. Васильева Л.Н. Совершенствование законодательства в области использования языков народов России // Журнал российского права. 2006. № 3. С. 5–8.

19. Prina, L. (2013) ‘Linguistic Rights in a Former Empire: Minority Languages and the Russian Higher Courts’, European Yearbook of Minority Issues, 10, pp. 82–83.

20. Ibid, pp. 79–81.

21. По улицам как по минному полю. В Петербурге судят тувинца, которого полицейские приняли за нелегального мигранта // Lenta.ru. 1 августа 2013. URL: https://lenta.ru/articles/2013/08/01/soskal/

22. Гармажапова А. Позор на весь мировой суд // Новая газета. 30 июля 2013. URL: https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2013/07/30/55723-pozor-na-ves-mirovoy-sud

23. Ольшанская О. В сыктывкарском суде с коми активистом отказались общаться на родном языке // Комсомольская правда. 12 февраля 2021. URL: https://www.komi.kp.ru/daily/27238/4366773/

24. В Казани состоялся очередной пикет за обязательное изучение татарского языка // Клуб регионов. 9 января 2023. URL: http://club-rf.ru/16/news/62145

25. Путин: «Заставлять человека учить язык, который для него родным не является, недопустимо» // Бизнес Online. 20 июля 2017. URL: https://www.business-gazeta.ru/news/352094

26. «Он хотел разбудить удмуртский народ» // Idel.Реалии. 12 июня 2022. URL: https://www.idelreal.org/a/31890562.html

27. Емельяненко В. Более 250 тысяч мусульман в мечетях Москвы встретили Ураза-байрам // Российская газета. 2 мая 2022. URL: https://rg.ru/2022/05/02/bolee-250-tysiach-musulman-v-mechetiah-moskvy-vstretili-uraza-bajram.html

28. «Приезжих меньше не становится» Подпольные мечети, давка и косые взгляды: как в Москве живут миллионы мусульман? // Мослента. 10 ноября 2021. URL: https://moslenta.ru/city/moskve-nuzhny-mecheti-ignorirovat-eto-ne-poluchitsya-zampred-soveta-muftiev-rossii-o-problemakh-musulman-v-stolice.htm

29. Емельяненко В. Более 250 тысяч мусульман в мечетях Москвы встретили Ураза-байрам // Российская газета. 2 мая 2022. URL: https://rg.ru/2022/05/02/bolee-250-tysiach-musulman-v-mechetiah-moskvy-vstretili-uraza-bajram.html

30. Патриарх назвал число храмов в Москве // РИА Новости. 22 декабря 2022. URL: https://ria.ru/20221222/khramy-1840526612.html

31. Как Башкирия отстояла Куштау (и потеряла БСК): хроника громких протестов в защиту шихана // Уфа1.ру. 15 августа 2021. URL: https://ufa1.ru/text/ecology/2021/08/15/70058681/

32. В Башкортостане трое защитников шихана Куштау получили до 7 лет условно // DOXA. 10 января 2023. URL: https://doxa.team/news/2023-01-10-bashkortostan

33. Башкирские националисты создают вооруженное сопротивление // Общая газета. 19 октября 2022. URL: https://obshchayagazeta.eu/ru/article/128045

34. Бессуднов А. Смертность российских военных в Украине: действительно ли этнические меньшинства погибают чаще? // BBC News. 28 октября 2022. URL: https://www.bbc.com/russian/features-63416259

35. Ляув Б., Соколов А., Базанова Е. Благоустройство Москвы в этом году оказалось дороже Крымского моста // Ведомости. 13 декабря 2019. URL: https://www.vedomosti.ru/economics/articles/2019/12/12/818607-blagoustroistvo-moskvi

36. Там само.

37. Газовые регионы России, и как обстоят их дела на сегодняшний день // Dprom.online. 25 ноября 2021. URL: https://dprom.online/oilngas/gazovye-regiony-rossii/#

38. Районы добычи нефти в России // Прогностика. URL: https://prognostica.info/news/rajony-dobychi-nefti-v-rossii/

39. Compare: Katz, A. and Sander, G. (2019) Staatsrecht: Grundlagen, Staatsorganisation, Grundrechte [State Law: Basics, State Organisation, Fundamental Rights]. Heidelberg: C.F. Müller.

40. Конституция Республики Татарстан от 6 ноября 1992 г. (с изменениями и дополнениями). URL: https://constitution.garant.ru/region/cons_tatar/chapter/1cafb24d049dcd1e7707a22d98e9858f/

41. Конституция (Основной Закон) Республики Саха (Якутия) (с изменениями и дополнениями). URL: https://constitution.garant.ru/region/cons_saha/chapter/1cafb24d049dcd1e7707a22d98e9858f/

42. Sumlenny, S. (2022) ‘Russia’s Collapse? Good News for Everyone’, CEPA, 25 October. Available at: https://cepa.org/article/russias-collapse-good-news-for-everyone/